Osteoporosis and Pilates

Osteoporosis and it’s precursor, osteopenia are common in both men and, more often, women during and after middle age. Causing weakened bones due to lower bone mass it has many causes including both diet and inactivity. Increasing levels of activity can arrest and even, to some extent reverse the loss of bone density. Pilates is ideal for this as it is weight bearing, controlled and all movements are carried out a careful and precise way.

However, there are some important caveats to bear in mind. Spinal flexion and to a lesser degree, rotation can be contraindicated and so any exercise programme needs to bear this in mind. A modified Pilates programme is an ideal way to tackle problems created by osteoporosis. However, don’t get disheartened, there are still hundreds of exercises that you can safely do: here is a list! (pdf)

Osteoporosis is extremely common

One in every two women and one in every four men aged 50 or older will suffer an osteoporosis-related hip, spine or wrist fracture during their lives. Among women over 50, 1 in every 2 has low bone density and is at risk of fracture.

Despite these statistics, in the UK, osteoporosis is not routinely screened for. The test is not only expensive but the initial cost of testing all women from say 50 to 80 years of age in the first year of screening means that universal screening for osteoporosis is unlikely to become reality.

Nonetheless, given that the osteoporotic vertebrae become so brittle, fractures can (but not necessarily) be caused by just the normal activities of everyday life. Bones weakened by the disease can fracture spontaneously or through such mild trauma as just coughing or sneezing.

This has tremendous implications not only for all exercise professionals but for everyone “middle aged” who wants to increase their level of physical activity.

What is Osteoporosis?

Osteoporosis is not a normal aging process but is the is the gradual loss of bone density. Osteopenia is mildly reduced bone mass–a loss of approximately 10%-20%–and it is an indicator of the onset of osteoporosis.

When you are tested (it’s called a DEXA), you receive a T-score. This tells you how your bone density compares to that of a 25-30 year old adult. A deviation of -1 to -2.5 below the mean indicates osteopenia. An SD of more than -2.5 indicates osteoporosis. For every 1-point drop below the mean, fracture risk doubles.

One of the problems of osteoporosis is that it is a “silent” disease. There are no outward symptoms as bone loss stays hidden until we see its effects through changes such as height loss or kyphosis.

People with with osteoporosis sometimes begin to find that their trousers are too long; or relatives notice that they are shrinking in height, they’re developing a hump or their arms look longer. Other people complain of waistline pain (caused when the ribs sit on the iliac crests), mid-back pain or neck pain. Hip pain is not common with osteoporosis and is present usually only after a fracture.

What causes bone loss?

Maybe we can understand the increasing rates of osteoporosis and fractures in the Western World when we stop to consider just how many risk factors there are for bone loss! Sedentary living and calcium deficiency are two major culprits, but there are many other causes.

Types of diseases that increase one’s risk of osteoporosis include genetic disorders, endocrine (including thyroid) disorders, gastrointestinal diseases, hematologic disorders, rheumatic and autoimmune diseases, alcoholism, smoking, congestive heart failure, emphysema, idiopathic scoliosis and multiple sclerosis. A quick Google search will reveal hundreds of possible causes, but what interests us most are the things that we can do to minimise the loss of bone density.

Lifestyle: exercise (a lot) and diet

People are discovering they have osteoporosis at younger and younger ages. It used to be a disease associated with the elderly, but not anymore.

Evidence suggests that lifestyle is a major culprit. In the developed world, we do not engage in physical activity, are becoming obese and do not take in enough nutrients to support good bone health. The incidence of osteoporosis in the developing world is significantly less.

We value convenience and time management and so we are increasingly sedentary. This is bad for our bones. Weight bearing activity is good for our bones.

One of my clients recently commented: “if I did all the exercises that I was asked to do, I’d have no time for life”. There’s a great deal to consider in that very pertinent observation!

Modern medicine can help, but individuals can do a great deal to promote bone our own bone health:

- engaging in regular weight-bearing exercise;

- following a bone-healthy diet;

- avoiding behaviours such as smoking and drinking excessive amounts of alcohol.

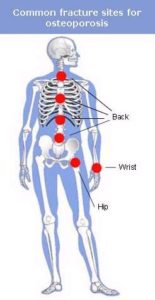

Where do fractures commonly occur?

The spine, hip and wrist are the most common site for osteoporosis related fractures.

The spine, hip and wrist are the most common site for osteoporosis related fractures.

The thoracic spine is the area of the spine at greatest risk of fracture. This is because, in contrast to the lower (lumbar) spine, the vertebrae are smaller and more delicate the higher you go up the spine. Another important reason is the curvature of the thoracic spine. This portion of the spine is in an anterior curve (bending forwards) that means that sections of the vertebral arch are closer together and more easily push against each other, thereby causing fractures. The most susceptible vertebrae to fracture are T7 T8 and T6 in that order.

However, tests do not usually show that there is osteoporosis present in the thoracic spine. Tests (DEXA) used to measure bone density cannot measure thoracic vertebrae bone density as it is surrounded by the sternum and ribs. If there is any degree of osteopenia or osteoporosis in the lumbar spine it has to be assumed that there is some, to a degree, in the thoracic spine.

Although we know that bone density decreases from the cervical to the lumbar spine. Bone size and ability to distribute force load decreases from the lumbar to the cervical spine. So if someone has osteopenia of the lumbar spine, an exercise specialist should assume that the person may have osteoporosis of the thoracic spine.

Exercise and the risks of fracture

All exercise specialists should use the same precautions for clients with osteopenia as for those with osteoporosis.

The study most quoted is that conducted by Sinaki & Mikkelsen (1984). They tested four separate groups of subjects with osteoporosis. Each group performed different types of exercise:

- Group 1: only extension exercises – bending backwards,

- Group 2: only flexion exercises – bending in a forward direction,

- Group 3: both extension and flexion exercises, and

- Group 4 did no exercises.

The results:

- Group 1 EXTENSION: 16% had another wedge or compression fracture

- Group 2 FLEXION: 89% had another wedge or compression fracture

- Group 3 EXT + FLEX: 53% had another wedge or compression fracture

- Group 4 NO EXERCISE: 67% had another wedge or compression fracture

The results speak for themselves. Sinaki & Mikkelsen found that 89% of the people who performed only flexion exercises suffered additional fractures during the study. Worse than doing no exercise at all!

This indicates that it is harmful and dangerous to perform flexion exercises when you have, or suspect osteoporosis! And given the high incidence of osteoporosis, makes one really think very carefully about what exercises people who fall into the high risk groups should be doing…

Forward bending (with rotation) is the dangerous movement!

Forward flexion, side-bending and especially forward flexion combined with rotation are therefore contraindicated for clients with osteoporosis–and hence, by extension, for everyone with osteopenia.

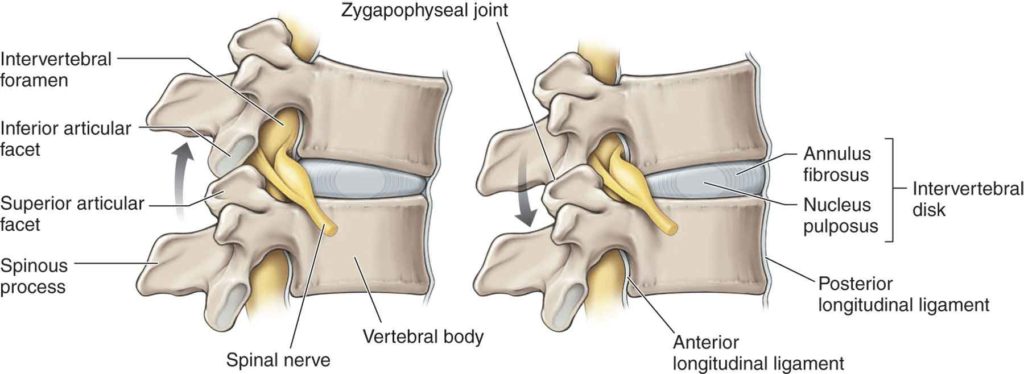

How does this work? The left hand diagram below shows forward flexion. Notice how the two vertebral bodies are closer together compared to the diagram on the right. In the left hand example, the intervertebral disk is compressed (as it should be). Conversely, on the right, the bony facets are compressed, leaving more space for the vertebral bodies.

One would think that compression of the bony protrusions would be the contraindicated movement. That is, the movement shown on the left.

But the bone that makes up the vertebral body is the is weaker (it’s known as cancellous bone) and is more affected by osteoporosis than that of the spinous processes and facets (cortical bone) that support the musculature of the spine.

Therefore, spinal extension is recommended. These muscle attachment points have a higher composition of cortical bone and are at a much lesser risk of fracture – despite the fact that they can rub together in extension exercises..

Not only that, but from these protrusion hang our spinal muscle groups: erector spinalis, multifidus, semispinalis, and rotators. Building strength in these muscle groups helps us to correct the “Dowager’s Hump” often associated with osteoporosis.

Developing stronger back extensor muscles will create higher bone density in your spine and hence fewer vertebral fractures and increased bone mineral density.

However!

The problem is that people intuitively avoid spinal extension because:

- of the “bone on bone” feeling during back arching;

- we tend to prefer flexion because it feels soft owing to the cushioning of the disks;

- spinal flexion is easier to do as the muscles in the front of our bodies are bigger and stronger

- muscle imbalances built up over a lifetime favour flexion over extension;

- “core” work is often associated with fitness and Pilates

- vanity: people want “abs”, not “spinals”

- Spinal extension is harder!

The Role of Effective & Guided Pilates Practice

Pilates is often suggested for building up bone strength, and for good reason. But is Pilates safe for someone with decreased bone density? In the process of trying to build up your bones, the instructor may well unwittingly cause microfractures that become a fully fledged fracture in time.

A programme of modified Pilates is required. Large group classes are not recommended unless they are specifically designed for people suffering from osteoporosis. Similarly, one on one classes should only be undertaken with an instructor of a proven record of knowledge in this area. Look for full and comprehensive training by Balanced Body, Stott, Polestar or BASI, and/or a copper-bottomed certification by Pilates Method Alliance (PMA).

Modified Pilates – finding a suitable instructor!

When clients with low bone density or newly healed fractures are ready to start a strengthening program, modified Pilates is an option. But safety must be paramount.

For maximum safety and benefit, it is crucial to follow these steps:

- Check with your doctor first before starting any exercise programme. The incidence of repeat fractures within one years is extremely high.

- Protect the Spine From Fracture. Before you begin a program, make sure your instructor clearly understands which moves are contraindicated and which are protective. Most important, learn to avoid all flexion, side-bending and rotation.

- Learn your Neutral and Optimal Spine Position. For some people, neutral spine will be impossible, in which case your instructor will need to teach you your optimal spinal position (as near neutral as possible – not necessarily imprinted). Check that your instructor knows how to do this.

- Learn the L-Shaped Hip Hinge. Ask your teacher to teach you the hip hinge to instruct clients how to disassociate spine movement from hip movement.

- Learn Proper Breathing. Learn costal (posterolateral – bucket-handle style) breathing. This encourages breathing into the lower back and in which the transversus abdominis muscles are contracted to prevent abdominal expansion or bulging, providing spinal support and stability of the pelvis.

After these steps, start your modified PIlates programme to build buff bones. Remember, exercise is never more useful than now and that exercise should still be fun!